Engaging Black girls in STEM learning through game design

Today is International Women’s Day, giving us the perfect opportunity to highlight a research project focusing on Black girls learning computing.

Between January and July 2021, we’re partnering with the Royal Academy of Engineering to host speakers from the UK and USA to give a series of research seminars focused on diversity and inclusion. By diversity, we mean any dimension that can be used to differentiate groups and people from one another. This might be, for example, age, gender, socio-economic status, disability, ethnicity, religion, nationality, or sexuality. The aim of inclusion is to embrace all people irrespective of difference. In this blog post, I discuss the third research seminar in this series.

This month we were delighted to hear from Dr Jakita O. Thomas from Auburn University and BlackComputHer, who talked to us about a seven-year qualitative study she conducted with a group of Black girls learning game design. Jakita is an Associate Professor of Computer Science and Software Engineering at Auburn University in Alabama, and Director of the CUlturally and SOcially Relevant (CURSOR) Computing Lab.

The SCAT programme

The Supporting Computational Algorithmic Thinking (SCAT) programme started in 2013 and was originally funded for three years. It was a free enrichment programme exploring how Black middle-school girls develop computational algorithmic thinking skills over time in the context of game design. After three years the funding was extended, giving Jakita and her colleagues the opportunity to continue the intervention with the same group of girls from middle school through to high school graduation (7 years in total). 23 students were recruited onto the programme and retention was extremely high.

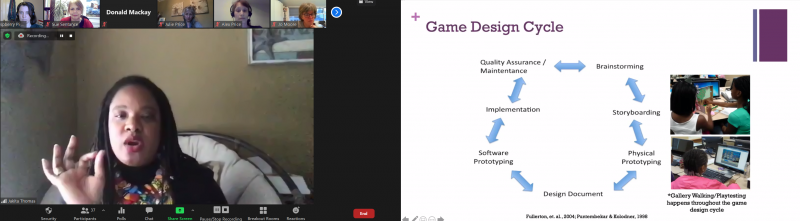

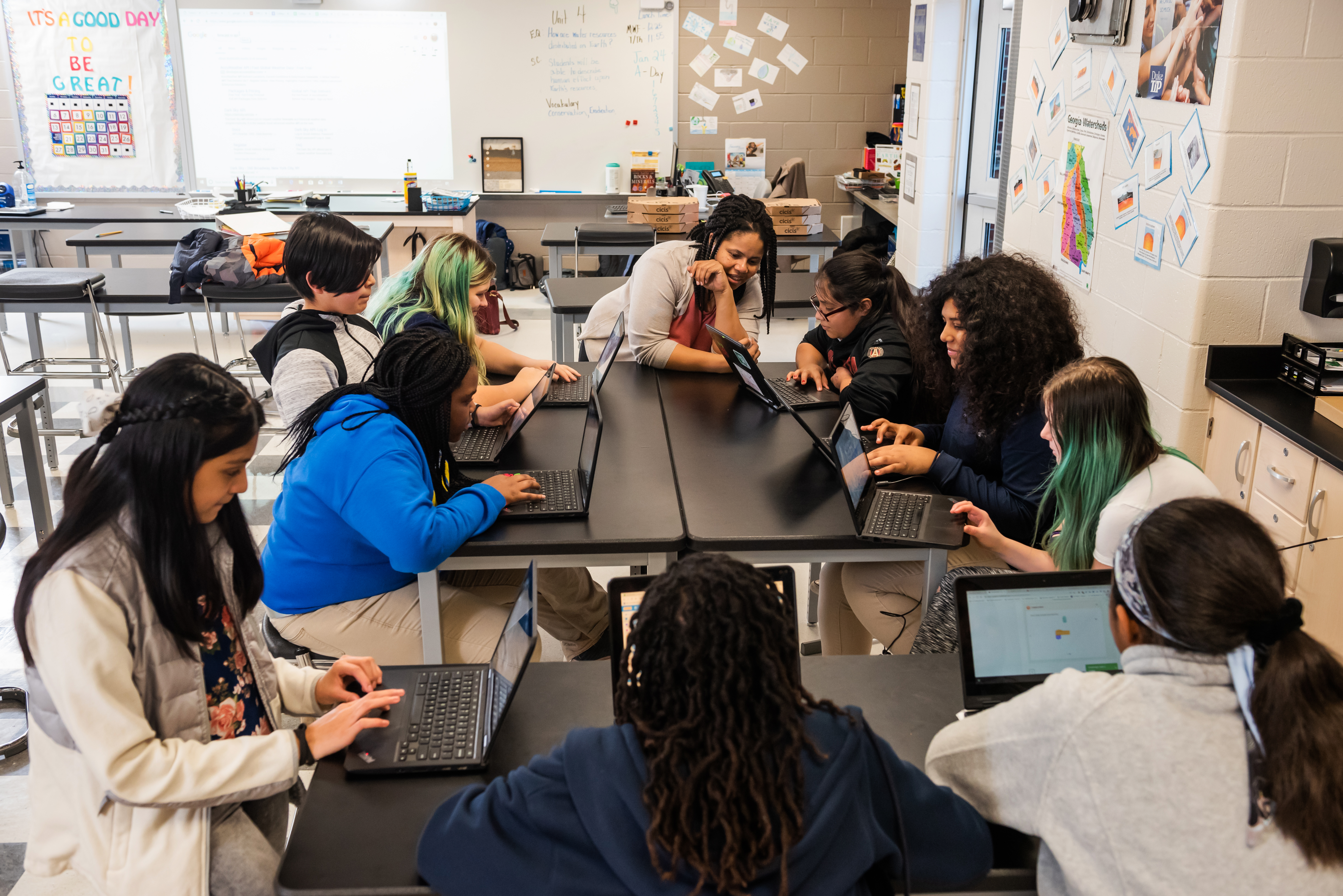

The SCAT programme ran throughout each academic year and also involved a summer camp element. The programme included three types of activities: the two-week summer camp, twelve monthly workshops, and field trips, all focused on game design. The instructors on the programme were all Black women, either with or working towards doctorates in computer science, serving as role models to the girls.

The theoretical basis of the programme drew on a combination of:

- Cognitive apprenticeship, i.e. learning from others with expertise in a particular field

- Black Feminist Thought (based on the work of Patricia Hill Collins) as a foundation for valuing Black girls’ knowledge and lived experience as expertise they bring to their learning environment

- Intersectionality, i.e. considering the intersection of multiple characteristics, e.g. race and gender

This context highlights that interventions to increase diversity in STEM or computing tend to support mainly white girls or Black and other ethnic minority boys, marginalising Black girls.

Why game design?

Game design was selected as a topic because it is popular with all young people as consumers. According to research Jakita drew on, over 94% of girls in the US aged 12 to 17 play video games, with little differences relating to race or socioeconomic status. However, game design is an industry in which African American women are under-represented. Women represent only 10 to 12% of the game design workforce, and less than 5% of the workforce are African American or Latino people of any gender. Therefore Jakita and her colleagues saw it as an ideal domain to work in with the girls.

Another reason for selecting game design as a topic was that it gave the students (the programme calls them scholars) the opportunity to design and create their own artefacts. This allowed the participants to select topics for games that really mattered to them, which Jakita suggested might be related to their own identity, and issues of equity and social justice. This aligns completely with the thoughts expressed by the speakers at our February seminar.

What was learned through SCAT?

Jakita explained that her findings suggest that the ways in which the SCAT programme was intentionally designed to offer Black girls opportunities to radically shape their identities as producers, innovators and disruptors of deficit perspectives. Deficit perspectives are ones that include implicit assumptions that privilege the values, beliefs, and practices of one group over another. Deficit thinking was a theme in our February seminar with Prof Tia Madkins, Dr Nicol R Howard, and Shomari Jones, and it was interesting to hear more about this.

Data sources of the project included analysis of online journal data and end of season questionnaires across the first three years of SCAT, which provided insights into the participants’ perceptions and feelings about their SCAT experience, their understanding of computational algorithmic thinking, their perceptions of themselves as game designers, and the application of concepts learned within SCAT to other areas of their lives outside of SCAT.

In the first three years of the programme, the number of participants who saw game design as a viable hobby went from 0% to 23% to 45%. Other analysis Jakita and her colleagues performed was qualitative and identified as one theme that the participants wanted to ‘find meaning and relevance in altruism’. The researchers found that the participants started to reflect on their own narrative and identity through the programme. One girl on the programme said:

“At the beginning of SCAT, I didn’t understand why I was there. Then I thought about what I was doing. I was an African American girl learning how to properly learn game design. As I grew over the years in game designing, I gained a strong liking. The SCAT program has gifted me with a new hobby that most women don’t have, and for that I am grateful.”

– SCAT scholar (participant)

Jakita explained that the girls on the programme had formed a sisterhood, in that they came to know each other well and formed a strong and supportive community. In addition, what I found remarkable was the long-term impact of this programme: 22 out of the 23 young women that took part in the programme are now enrolled on STEM degree courses.

What next?

Read the paper on which Jakita’s seminar was based, download the presentation slides, and watch the video recording:

This research intervention obviously represents a very small sample, as is often the case with rich, qualitative studies, but there is much we can learn from it, and still much more to be done. In the UK, we do not have any ongoing or previously published research studies that look at intersectionality and computing education, and conducting similar research would be valuable. Jakita and her colleagues worked in the non-formal space, providing opportunities outside the formal curriculum, but throughout the academic year. We need to understand better the affordances of non-formal and formal learning for supporting engagement of learners from underrepresented groups in computing, perhaps particularly in England, where a mandatory computing curriculum from age 5 has been in place since 2014.

Next up in our free series

This was our 14th research seminar! You can find all the related blog posts on this page.

Next we’ve got three online events coming up in quick succession! In our seminar on Tuesday 20 April at 17:00–18:30 BST / 12:00–13:30 EDT / 9:00–10:30 PDT / 18:00–19:30 CEST, we’ll welcome Maya Israel from the University of Florida, who will be talking about Universal Design for Learning and computing. On Monday 26 April, we will be hosting a panel session on gender balance in computing. And at the seminar on Tuesday 2 May, we will be hearing from Dr Cecily Morrison (Microsoft Research) about computing and learners with visual disabilities.

To join any of these free events, click below and sign up with your name and email address:

We’ll send you the link and instructions. See you there!

3 comments

Dale Steele

Thanks for sharing these important programs and research findings. Please keep up this work.

Sue Sentance — post author

Thanks Dale!

Lyle Stephens

The scat programme sounds fantastic.