Non-formal learning activities: What do we know and how do we apply it to computing?

At the Raspberry Pi Foundation, we engage young people in learning about computing and creating with digital technologies. We do this not only by developing curricula for formal education and introducing tens of thousands of children around the world to coding at home, but also through supporting non-formal learning activities such as Code Club and CoderDojo.

To find out what works in non-formal computing learning, we’ve conducted two research projects recently: a systematic literature review, and a set of two interventions that were applied and evaluated as part of our Gender Balance in Computing programme. In this blog, we outline these two research projects.

What is non-formal learning?

When you think of young people learning computing, do you think of schools, classrooms, and curricula? You’d be right that lots of computing education for young people takes place in classrooms as part of national curricula. However, a lot of learning can take place outside of formal schooling. When we talk about non-formal computing education, we mean structured or semi-structured learning environments such as clubs or community groups, often set up by volunteers. These may take place in a school, library, or community venue; but we’ve also heard of some of our communities running non-formal learning activities on buses, in fire stations, or at football grounds — there really is no limit to where learning can happen.

It’s harder to assess the impact and effectiveness of non-formal computing activities than formal computing education: we have to think outside of the traditional measures such as grades and formal exams or assessments. Instead, we estimate outcomes according to measures such as level of participant engagement, attendance, attrition rates, and changes in participants’ attitudes towards computing. We have previously also piloted non-formal assessments such as quizzes and found that these were well-received by adult facilitators and children alike.

Project 1: Researching the impact of non-formal computing education

Earlier this year, we conducted a systematic literature review into computing education for K–12 learners in non-formal settings. We identified 88 relevant research studies, which we read, compared, and synthesised to provide an overview of what is already known about the effectiveness of non-formal computing activities and to identify opportunities for further research.

Our analysis looked for common themes within existing studies and suggested some benefits that non-formal learning offers, including:

- Access to advanced and innovative topics

- Awareness about computing careers

- The chance to personalise projects according to learner interests

- The opportunity for learners to progress at their own pace

- The chance for learners to develop a sense of community through peers and role models

We presented this research at an international computing education conference called ICER 2022, and you can read about it in our open-access paper in the ICER conference proceedings.

Project 2: Making links between non-formal learning and formal computing study skills

One particularly interesting characteristic of non-formal learning is that it tends to attract a broader range of learners than formal computing lessons. For example, a 2019 survey found that about 40% of the young people who attend Code Clubs were female. This is a high percentage compared with the proportion of girls among the learners choosing Computer Science GCSE in England, which is currently around 20%. We believe this points to an opportunity to capitalise on girls’ interest in learning activities outside of the classroom, and we hope to use non-formal activities to encourage more girls to take an interest in formal computer science education.

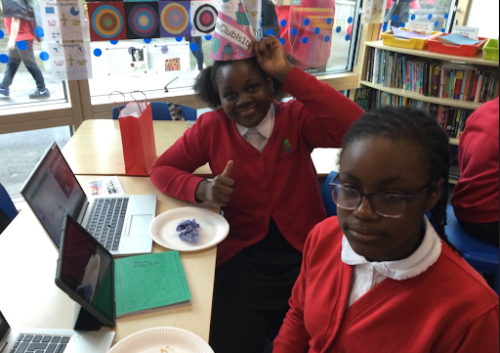

As part of our Gender Balance in Computing research programme in England, we worked with Apps for Good and the Behavioual Insights Team (BIT) to run two interventions in school-based non-formal settings, for which we adapted non-formal resources and used behavioural science concepts to strengthen the links the resources make between non-formal learning and studying computing more formally. One intervention ran in secondary schools for learners aged 13–14 years old, who used an adapted Apps for Good course, and the other ran in primary school for learners aged 8–11 year olds, who took part in Code Clubs using adapted versions of our projects.

The interventions were evaluated independently by a separate team from BIT, based on data from surveys completed by learners before and after the interventions, and interviews with teachers and learners. This data was analysed by the independent team to explore the impact the interventions had on learners’ attitudes towards computing and intention to study the subject in the future.

What did we learn from these research projects?

Our literature review concluded that future research in this area would benefit from experimenting with a variety of approaches to designing, and measuring the impact of, computing activities in a non-formal setting. For example, this could include comparing the short-term and long-term impact of specific interventions, aiming to cater for different types of participants, and offering different types of learning experiences.

In these two Gender Balance in Computing interventions, there was limited statistical evidence of an improvement in participants’ attitude towards computing or in their stated intention to study computer programming in the future. The independent evaluators recommended that the learning content that was created for the interventions could be adapted further to make the link between non-formal and formal learning even more salient. On the other hand, as is often the case with research, some interesting themes — ones that we weren’t looking for — emerged from the data, including:

- In the secondary school intervention, there was a small, positive change in girls’ attitudes toward computing when they saw that it was relevant to real-world problems

- In the primary school intervention, some teachers also reported an increased confidence to pursue computing among girls who had used the adapted Code Club resources, and they highlighted the importance of positive female role models in computing

In both projects, the findings suggest that it is beneficial for learners to participate in non-formal learning activities that link to real-world situations, and that this could be particularly beneficial for girls to help them see computing as a subject that is relevant to their own interests and goals. Another common theme in both projects is that non-formal learning activities play an important role in showing what a “computer person” looks like and who belongs in computing. This suggests there’s a need for a diverse range of volunteers to run non-formal computing activities, and that we should make sure that non-formal learning resources include representations of a diverse range of learners.

Undertaking these research projects has provided evidence that the work the Foundation does is on the right track and suggested opportunities to use these themes in our future non-formal work and resources.

Find out more about our work on non-formal computing education

- Read the full evaluation reports from the non-formal learning interventions in primary schools and secondary schools

- Find out more about the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s non-formal learning initiatives: Code Club, CoderDojo, the European Astro Pi Challenge, and the Coolest Projects showcases

- Sign up for our free seminar on Tuesday 8 November to hear about further research work on non-formal learning from Dr Tracy Gardner and Rebecca Franks on our team

More information about research projects at the Raspberry Pi Foundation and our newly launched Raspberry Pi Computing Education Research Centre can be found on our research pages and on the Research Centre’s website.

No comments