‘Gender Balance in Computing’ research project launch

I am excited to reveal that a consortium of partners has been awarded £2.4 million for a new research project to investigate how to engage more girls in computing, as part of our work with the National Centre for Computing Education. The award comes at a crucial time in computing education, after research by the University of Roehampton and the Royal Society recently found that only 20% of computing candidates for GCSE and 10% for A level Computer Science were girls.

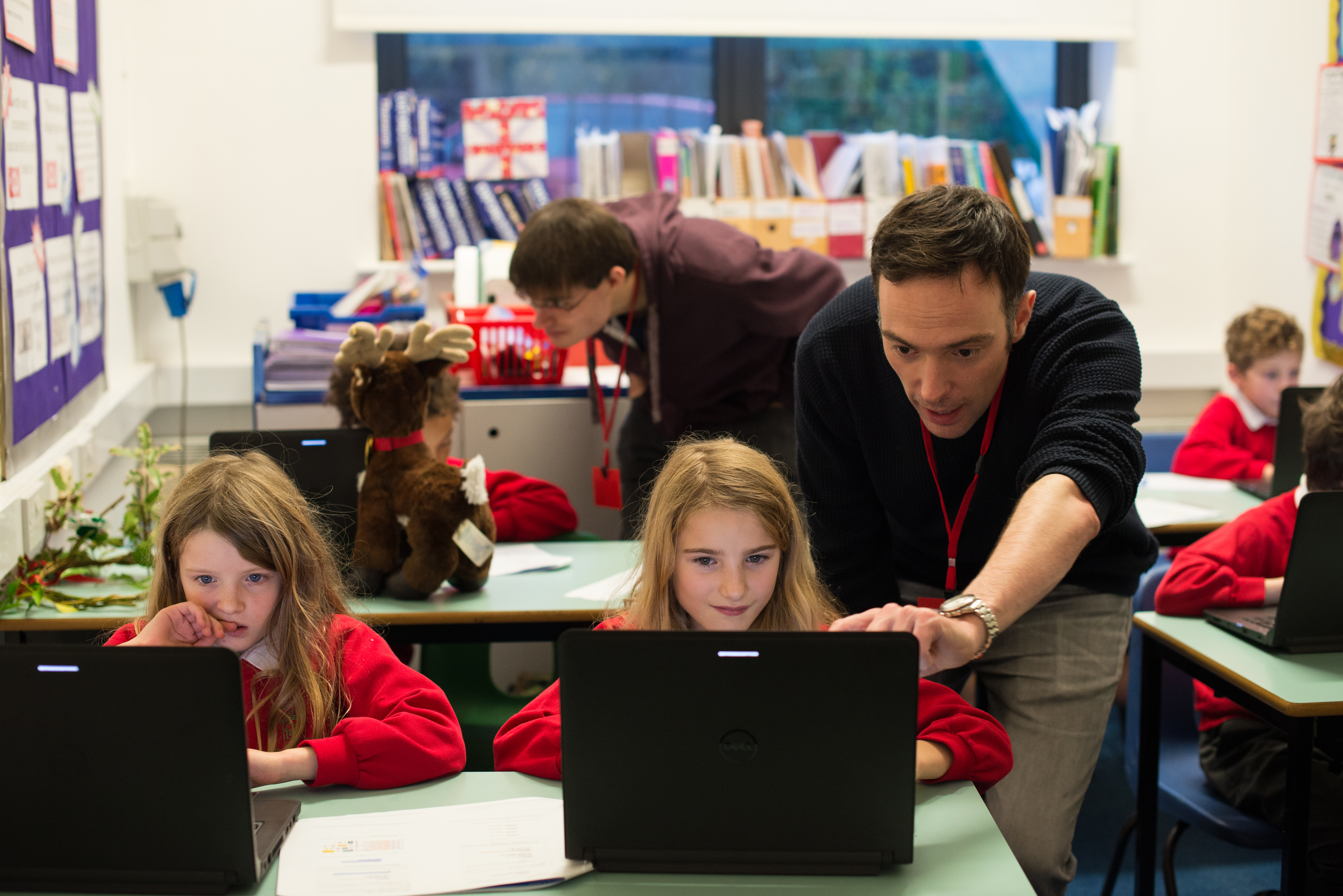

The project will investigate ways to make computing more inclusive.

The project

‘Gender Balance in Computing’ is a collaboration between the consortium of the Raspberry Pi Foundation, STEM Learning, BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT, and the Behavioural Insights Team. Our partners, Apps for Good and WISE, will also be working on the project. Trials will run from 2019–2022 in Key Stages 1–4, and more than 15,000 students and 550 schools will be involved. It will be the largest national research effort to tackle this issue to date!

Our research around gender balance has many synergies with the work of the wider National Centre for Computing Education (NCCE) programme, which also focuses on pedagogy and widening participation. We will also be working with NCCE Computing Hubs when planning and implementing the trials.

How it will work

‘Gender Balance in Computing’ will develop and roll out several projects that aim to increase the number of girls choosing to study a computing subject at GCSE and A level. The consortium has already identified some of the possible reasons why a large percentage of girls don’t consider computing as the right choice for further study and potential careers. These include: feeling that they don’t belong in the subject; not being sufficiently encouraged; and feeling that computing is not relevant to them. We will go on to research and pilot a series of new interventions, with each focusing on addressing a different barrier to girls’ participation.

We will also trial initiatives such as more inclusive pedagogical approaches to teaching computing to facilitate self-efficacy, and relating informal learning opportunities, which are often popular with girls, to computing as an academic subject or career choice.

Signposting the links between informal and formal learning is one of the interventions that will be trialled.

Introducing our partners

WISE works to increase the participation, contribution, and success of women in the UK’s scientific, technology, and engineering (STEM) workforce. Since 1984, they have supported young women into careers in STEM, and are committed to raising aspirations and awareness for girls in school to help them achieve their full potential. In the past three years, their programmes have inspired more than 13,500 girls.

The Behavioural Insights Team have worked with governments, local authorities, businesses and charities to tackle major policy problems. They generate and apply behavioural insights to inform policy and improve public services.

Apps for Good has impacted more than 130,000 young people in 1500 schools and colleges across the UK since their foundation in 2010. They are committed to improving diversity within the tech sector, engaging schools within deprived and challenging contexts, and enthusing girls to pursue a pathway in computing; in 2018, 56% of students participating in an Apps for Good programme were female.

“A young person’s location, background, or gender should never be a barrier to their future success. Apps for Good empowers young people to change their world through technology, and we have a strong track record of engaging girls in computing. We are excited to be a part of this important work to create, test, and scale solutions to inspire more girls to pursue technology in education. We look forward to helping to build a more diverse talent pool of future tech creators.” — Sophie Ball & Natalie Moore, Co-Managing Directors, Apps for Good

The Raspberry Pi Foundation has a strong track record for inclusion through our informal learning programmes: out of the 375,000 children who attended a Code Club or a CoderDojo in 2018, 140,000 (37%) were girls. This disparity between the gender balance in informal learning and the imbalance in formal learning is one of the things our new research project will be investigating.

The challenge of encouraging more girls to take up computing has long been a concern, and overcoming it will be critical to ensuring that the nation’s workforce is suitably skilled to work in an increasingly digital world. I’m therefore very proud to be working with this group of excellent organisations on this important research project (and on such a scale!). Together, we have the opportunity to rigorously trial a range of evidence-informed initiatives to improve the gender balance in computing in primary and secondary schools.

If you work at a school in England you can register your interest in taking part in this project here.

13 comments

Linda Luo

Hey, Please check out WomenInPython here

https://github.com/saulomeirelles/WomenInPythonShenzhen

Andrew

There seems to a correlation between societies with high levels of gender equality and low levels of participation of girls in STEM subjects. Societies with the lowest levels of gender equality have the highest levels of female participation in the STEM field.

Stoet, G. and Geary, D. C. (2018) ‘The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education’, Psychological Science, 29(4), pp. 581–593. doi: 10.1177/0956797617741719.

The conclusion drawn is that when girls have the most freedom to choose their courses and careers they tend to choose subjects other than STEM.

“One of the main findings of this study is that, paradoxically, countries with lower levels of gender equality had relatively more women among STEM graduates than did more gender equal countries. This is a paradox, because gender-equal countries are those that give girls and women more educational and empowerment opportunities, and generally promote girls’ and women’s engagement in STEM fields (e.g., Williams & Ceci, 2015).”

Having low and falling rates of women’s participation in the STEM field may well be a sign that you live in a progressive country with a high level of gender equality. The countries in the study with the lowest female participation rates in the STEM field included; Sweden, Norway, Finland, Netherlands and Switzerland. The countries with the highest rates of female participation in the STEM field in this study included; Algeria, Tunisia, Turkey, UAE and Albania.

This study would not seem to support the assumption that girls, when given the most freedom, encouragement and support to choose their school subjects and career paths, would naturally choose STEM subjects at the same rate as boys. It appears to suggest the greater freedom they have to choose, the lower their participation in STEM.

John Sibbald

Really interesting!

I’ve been working with some International students at INTO Manchester (students take an A-level equivalents in English then apply to Universities) and many of the girls who want to go into STEM are from the coutries you list icluding Russia.

Do you have any pointers to more research on this?

Raspberry Pizza

I’ve been talking to my daughter about this, she is doing a sociology A level and this is one of the things that they have been discussing in their studies.

The opinion of her peer female students seems to be that (heavily generalising) they regard the STEM subjects and the people that excel in them with some derision and the attached terms like “nerd” and “geek” tend to be repellent. As Andrew says in his comment, if the nation is developed so as to allow them to earn a living by another more appealing career, then they tend to be attracted to other work.

Terry Critchley

I have commented at length of this at the base of this article but it does not seem to have appeared. Censored?

tcritchley07 at gmail dot com

Raspberry Pi Staff Liz Upton

Nope, just not very many people around to moderate this bank holiday weekend! We work with CAS very closely, by the way; check out our About page.

pete

I also made a comment on this post last week and it hasn’t come up … Was there a problem with the website over the weekend?

Raspberry Pi Staff Liz Upton

Not as far as I’m aware; because you’ve made posts we’ve approved before, any comments from you should be published automatically. I’ve looked in the spam and trash folders, and there’s nothing from you there; are you quite sure you hit the submit button? There are no comments pending.

(The other poster’s just referring to having had to wait a few hours for his post to be approved and published. On a weekend, especially a bank holiday weekend, we’re not checking for comments here as frequently as usual. It’s disheartening that someone’s first reaction to not getting something approved immediately is to announce that they’re being censored, but hey – welcome to the internet in 2019.)

Li

Surely then the question has to be asked, where is the perception of those girls (that STEM is not ‘appealing’) coming from? How much of it is unconscious (or deliberate) bias being taught to them by that ‘developed’ society, either from peers or adults?

The correlation/causation relationship *may* be the other way around, or erroneous. Just because a country is more developed in terms of generally allowing girls more freedom to work, doesn’t mean it’s also more developed in terms of not biasing them towards or away from certain jobs. Ergo, if more girls have freedom to choose a career, but an underlying bias about what roles they ‘should’ play remains, it seems logical that more girls will appear to be gravitating away from STEM when in fact it’s just a matter of more girls being able to choose a career but choosing the path of least resistance, or the path that’s presented to them.

It may be that ‘gender-equal countries… generally promote girls’ and women’s engagement in STEM fields’, but the key word there is ‘generally’, and the unmentioned points are: how *much* do they promote said engagement; how does it compare to promoting that engagement to boys; and is unconscious societal bias, outside of the direct career-choosing process, taken into account? I would argue that there’s still no such thing as a ‘gender-equal’ country, and career choice doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

It’s an unanswerable question of course, but if girls were brought up to the point of choosing a career with a complete lack of any gender role bias and every opportunity presented equally, I wonder how much different their perception of what’s ‘appealing’ would be?

Rich Steed

How can schools get involved with this? I’ve been trying to get more girls into GCSE Computer Science for years with some results but still not enough!

Never had a female A Level student yet!

Raspberry Pi Staff Janina Ander

The National Centre for Computing Education is setting up an email address which interested schools can contact to register their interest. The address will be announced on the NCCE’s Twitter account, so keep an eye out: https://twitter.com/WeAreComputing

Terry Critchley

I can’t find any mention of the survey that CAS carried out on why females shun computing as a subject and career. I devised the survey, which CAS modified s little and sent it out.

CAS: FEMALES AND COMPUTING/COMPUTER SCIENCE SURVEY (2018)

http://community.computingatschool.org.uk/files/9958/original.pdf

I based my questions of a) my nearly 50 years in coal-face computing and b) the belief that asking females students directly why they shunned computing was the way to go. The main themes of the responses were;

1. It is boring

2. It requires too much maths

Both are incorrect assumptions about real computing in the workplace, where I spent my career and now write about in books and articles. This is the alpha and omega of the dilemma and unless computer training reflects what the workplace needs, the dilemma will persist. I am tired of saying this but as it is the truth, I shall press on.

There is a train of CAS thought which says that computer science is a discipline and not a route to employment; if that is the situation, then so be it but the fact that many girls in the survey asked about salaries means that they are interested in career options but not via CS.

Forget further surveys (scores of them have already been done with no conclusions). The survey I mention above allowed ‘free form’ input and did not always lead with Yes or No questions which can lead to erroneous conclusions even though the surveyor may not be aware of his/her unknowing bias.

If you don’t believe me, just carry on surveying and surmising about this issue but it will lead nowhere unless the destination for CS studies is defined; academic or workplace?

Ali

At my children’s school very few other children want to do computing at all and the computer class for GCSE is under subscribed.

Those who are doing computing are almost all boys.

Also, almost all the children with autistic related SEN from my eldest’s year are doing computing and they are all boys.

So any child thinking of taking GCSE Computing can look at the year above and see a class full of socially awkward boys who find it easier to type on a keyboard than talk to someone.

Is there a link between Autism and Computing? Is there one between Autism and Boys? Google says yes:

https://www.autismag.org/autism-in-boys/

85% of autism diagnosis are for boys

https://scips.worc.ac.uk/subjects-and-disabilities/computing-comp_autism/

Autistic people naturally relate to computers