Embodied machine learning: From research ideas to classroom activities

Where do great research ideas come from in computer science education? We might think of research breakthroughs as a single moment of genius, but in reality impactful research is often the result of many years of iterative development. In November’s research seminar, we heard from Karl-Emil Kjær Bilstrup, a researcher at the University of Copenhagen, about his work to develop ML-Machine. This work uses embodied learning principles and the BBC micro:bit to introduce learners to machine learning concepts. Findings from this research have been used to develop the micro:bit CreateAI resources, and in this blog, we will explain the research journey from initial small-scale work to educational resources used by many young learners around the world.

From hypothetical ethics to concrete machines

In Karl-Emil’s first research study, students used prompt cards to develop ideas for machine learning applications that could solve real-world problems, and to discuss the ethical dilemmas associated with their solutions. Students found it difficult to address these ethical dilemmas in their designs; for example, their ideas often featured a trade-off of user privacy. The findings from this research informed Karl-Emil’s next study, which moved from hypothetical scenarios to implementing machine learning in real-world settings.

The ‘Machine Learning Machine’ study made machine learning processes tangible for students through the use of two physical boxes, shown in the picture below. Students created drawings and fed them into the first box to train a model, and then tested the model by placing new drawings under a camera in the second box and having the model produce predictions of what the drawings showed. For example, students could draw pictures of the sun to represent daytime and the moon to represent nighttime to train a model to predict whether new drawings represented day or night. The machine was built for slow interaction, giving students time to think about the concepts and practices that they were developing. In a follow-up study, a new version of the Machine Learning Machine had been designed, which was controlled using a graphical user interface (GUI). This allowed users to “unbox” and influence parts of the machine learning process. For example, students could adjust the number of complete passes (called ‘epochs’) through the training data to improve the model’s accuracy.

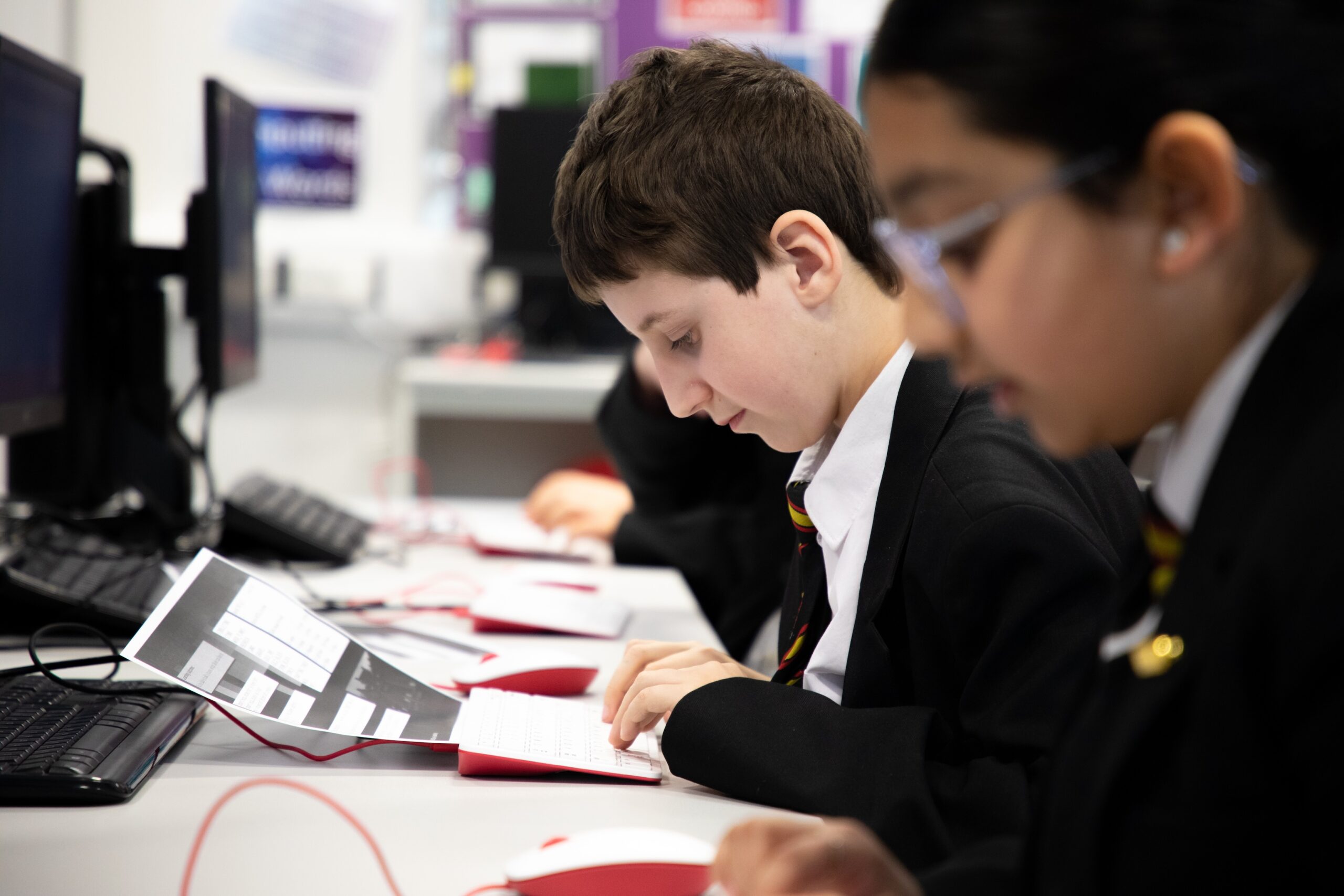

The two studies with the Machine Learning Machines provided many useful findings for teaching about machine learning with K–12 (primary and secondary) learners. However, two constraints remained: firstly, there were limited opportunities for whole-class work because there was only one Machine Learning Machine, and secondly, learning experiences needed to be better connected to examples from students’ daily lives. As a result, the next iteration in Karl-Emil’s research involved using the micro:bit, which ensured access to a tangible device for every student, and a new graphical platform called ML-Machine that students could interact with.

Machine learning and the micro:bit

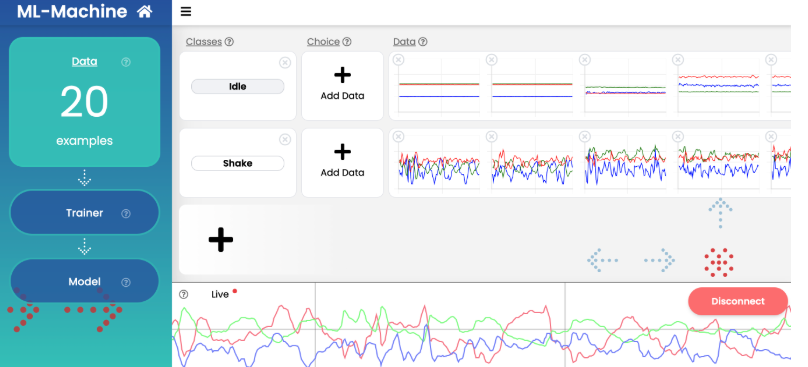

The micro:bit is a small, programmable computing device that features sensors to gather data from the immediate environment. For example, the accelerometer is a motion sensor that can detect when the micro:bit is tilted from left to right, backwards and forwards, and up and down. Using the micro:bit with ML-Machine and some common household objects, students can create simple machine learning models that use data from the micro:bit’s accelerometer to detect whether the micro:bit is moving. This is a very different approach from rule-based programs on the micro:bit, where students might use programming constructs such as if statements to detect movement if the numerical reading from the accelerometer is above a certain value. Here, a machine learning model trained using a set of 20 examples is used to analyse live data readings and produce predictions about whether the micro:bit is moving.

In our seminar, Karl-Emil gave a live demonstration of the ML-Machine toolkit, so we highly recommend watching the recording to see how this toolkit brings machine learning concepts to life.

ML-Machine is the precursor to the micro:bit CreateAI resources, and the software is fully open-source. However, the innovation doesn’t stop there: Karl-Emil also explained that he is currently developing a new tool called math.ml-machine.org, where students can train a neural network and see a visualised k-nearest neighbour model to explore how a model makes predictions. The research journey is continuing, with new possibilities for educational opportunities to teach about machine learning.

Embodied learning

The idea of embodied learning is interwoven throughout all of Karl-Emil’s research projects and is a cornerstone of all of his work. Embodied learning suggests that we learn more effectively when our whole body is involved in the learning process, not just our minds. For example, in the work described in this seminar, the Machine Learning Machines and the micro:bit were all tangible devices that students could touch and see.

Embodied learning is particularly important in activities that involve working with data-driven systems. In traditional programming activities, the flow of code can be traced transparently through a program. However, machine learning models are more opaque, and their outputs cannot be traced step by step. Students can benefit from using bodily movements and sensorimotor information to help understand machine learning concepts.

The ML-Machine toolkit was designed to support students to learn through embodied learning in three different ways:

- Enacting machine learning processes: Students used bodily movement to collect the data samples needed for the ML-Machine model to detect and predict gestures

- Using machine learning as a design material: Students created concrete ‘objects-to-think-with’, which helps form deeper connections to abstract concepts

- Embodied exploration of machine learning: Students experienced how their bodily movements were translated into data points on the screen

Embodied learning helped students grasp concepts such as data quality. They could see how their bodily movements were being translated into digital data, and could spot when movements that appeared different to them were being classified as similar by the ML-Machine model. One case study participant described that the immediate feedback on screen made the concept of machine learning feel as if it were “coming to life as they [the students] manipulate something themselves and they’ve got control over it”.

Find out more

Karl-Emil’s work shows how research ideas can be used in the classroom through a cycle of discovery, design, and reflection. From prompt cards exploring ethics to tangible machines and the micro:bit-based ML-Machine, his research shows how embodied learning can make complex ideas like machine learning not only understandable, but deeply engaging for young learners. The micro:bit CreateAI resources are a great example of how research findings can evolve into accessible, hands-on tools that empower educators and students alike. As this work continues to grow, it invites us to imagine new ways for learners to experience machine learning not as abstract theory, but as something they can see, feel, and shape with their own hands.

If you’d like to try out some of the ideas from this seminar, here are some useful resources:

- Explore machine learning projects using the micro:bit: micro:bit CreateAI and our Dance detector project are great places to start

- Find out more about the research: Read more about Karl-Emil’s work in this open-access paper

- Investigate new tools: Explore neural networks and k-nearest neighbours algorithms in the new maths-focused version of ML-Machine at math.ml-machine.org

Join our next seminar

Join us at our next seminar on Tuesday 17 March from 17:00 to 18:30 GMT to hear Rebecca Fiebrink (University of the Arts London speak about teaching AI for creative practitioners. This will be the second seminar in our new series on how to teach about AI across disciplines. We hope to see you there!

To sign up and take part in our research seminars, click below:

You can also view the schedule of our upcoming seminars, and catch up on past seminars on our previous seminars page.

No comments

Jump to the comment form