Secondary school maths showing that AI systems don’t think

At a time when many young people are using AI for personal and learning purposes, schools are trying to figure out what to teach about AI and how (find out more in this summer 2025 data about young people’s usage of AI in the UK). One aspect of this is how technical we should get in explaining how AI works, particularly if we want to debunk naive views of the capabilities of the technology, such as that AI tools ‘think’. In this month’s research seminar, we found out how AI contexts can be added to current classroom maths to make maths more interesting and relevant while teaching the core concepts of AI.

At our computing education research seminar in July, a group of researchers from the CAMMP (Computational and Mathematical Modeling Program) research project shared their work:

- Prof. Dr. Martin Frank, Founder of CAMMP (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany).

- Assistant Prof. Dr. Sarah Schönbrodt (University of Salzburg, Austria)

- Research Associate Stephan Kindler (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany)

They talked about how maths already taught in secondary schools can be used to demystify AI. At first glance, this seems difficult to do, as it is often assumed that school-aged learners will not be able to understand how these systems work. This is especially the case for artificial neural networks, which are usually seen as a black box technology — they may be relatively easy to use, but it’s not as easy to understand how they work. Despite this, the Austrian and German team have developed a clear way to explain some of the fundamental elements of AI using school-based maths.

Sarah Schönbrodt started by challenging us to consider that learning maths is an essential part in developing AI skills, as:

- AI systems using machine learning are data-driven and are based on mathematics, especially statistics and data

- Authentic machine learning techniques can be used to bring to life existing classroom maths concepts

- Real and relevant problems and associated data are available for teachers to use

A set of workshops for secondary maths classrooms

Sarah explained how the CAMMP team have developed a range of teaching and learning materials on AI (and beyond) with an overall goal to “allow students to solve authentic, real and relevant problems using mathematical modeling and computers”.

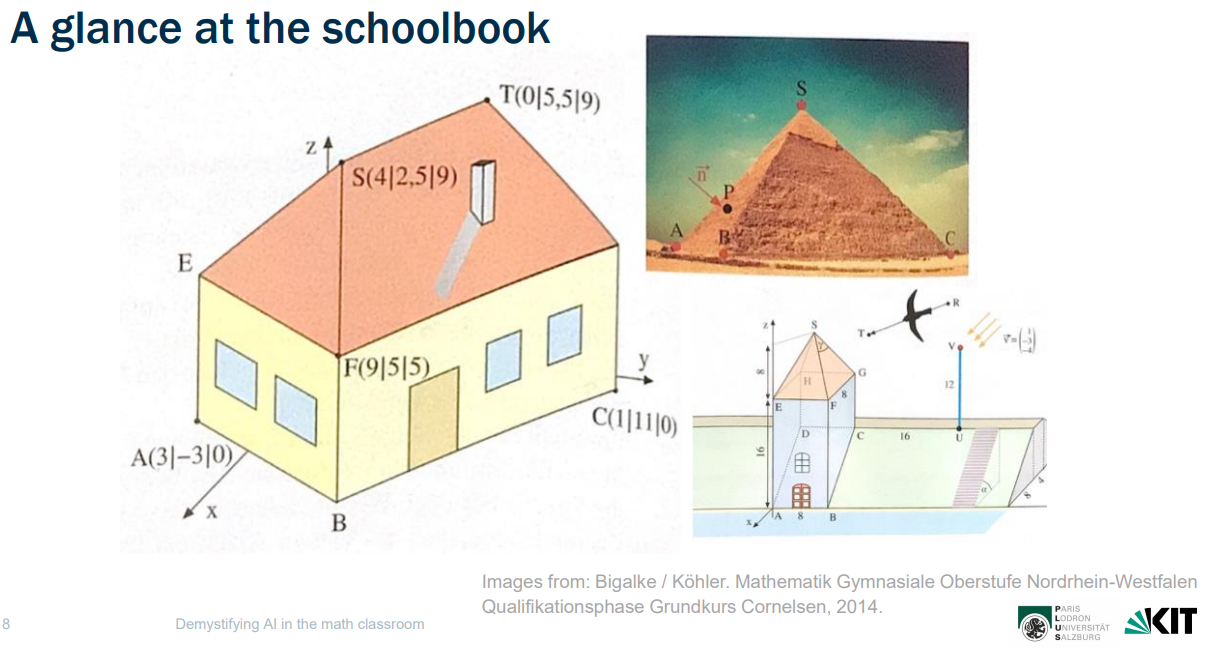

She reflected that much of school maths is set in contexts that are abstract, and may not be very interesting or relevant to students. Therefore, introducing AI-based contexts, which are having a huge impact on society and students’ lives, is both an opportunity to make maths more engaging and also a way to demystify AI.

Workshops designed and researched by the team include contexts such as privacy in social networks to learn about decision trees, personalised Netflix recommendations to learn about k-nearest neighbour, word predictions to learn about N-Grams, and predicting life expectancy to learn about regression and neural networks.

Learning about classification models: traffic lights and the support vector machine

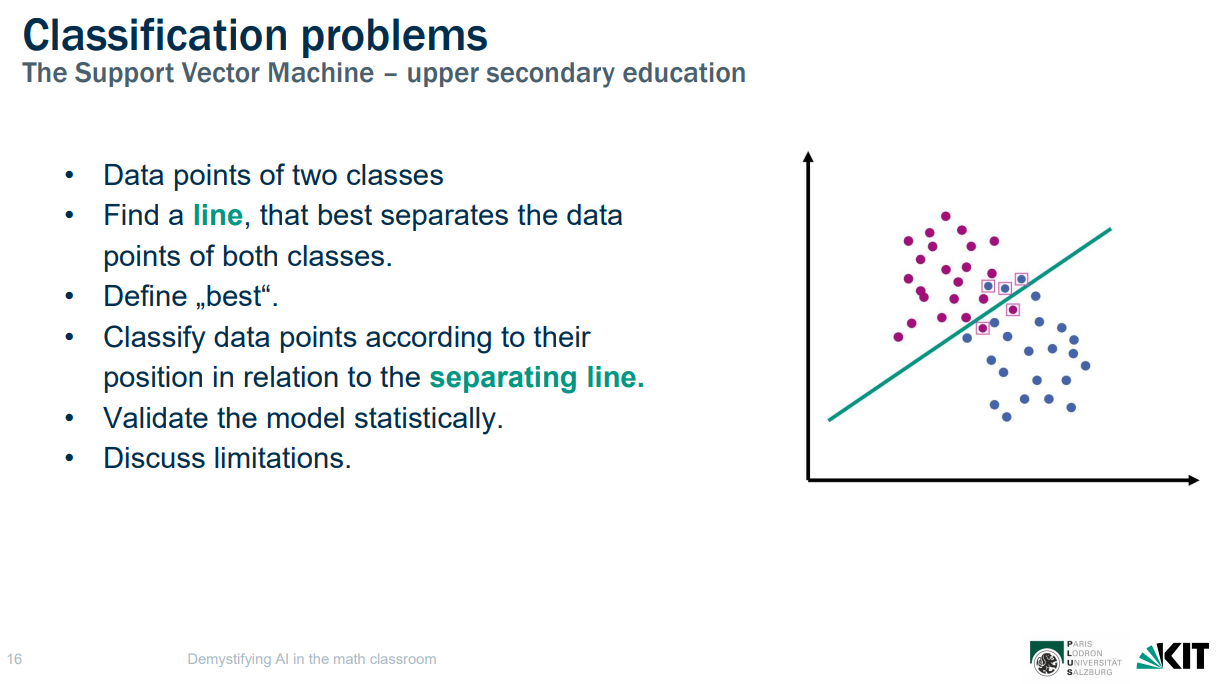

For the seminar, Sarah walked through the steps to learn about support vector machines. This is an upper secondary workshop for students aged 17 to 18 years old. The context of the lesson is an image problem — specifically, classifying the data representing the colours of a simplified traffic light system (two lights to start with) to work out if a traffic light is red or green.

She walked through each of the steps of the maths workshop:

- Plotting data points of two classes, the representation of green and red traffic lights

- Finding a line that best separates the data points of both classes

- Figuring out what best is

- Classifying the data points in relation to the chosen (separating) line

- Validating the model statistically to see if it is useful in classifying new data points, including using test data and creating a contingency table (also called a confusion matrix)

- Discussing limitations, including social and ethical issues

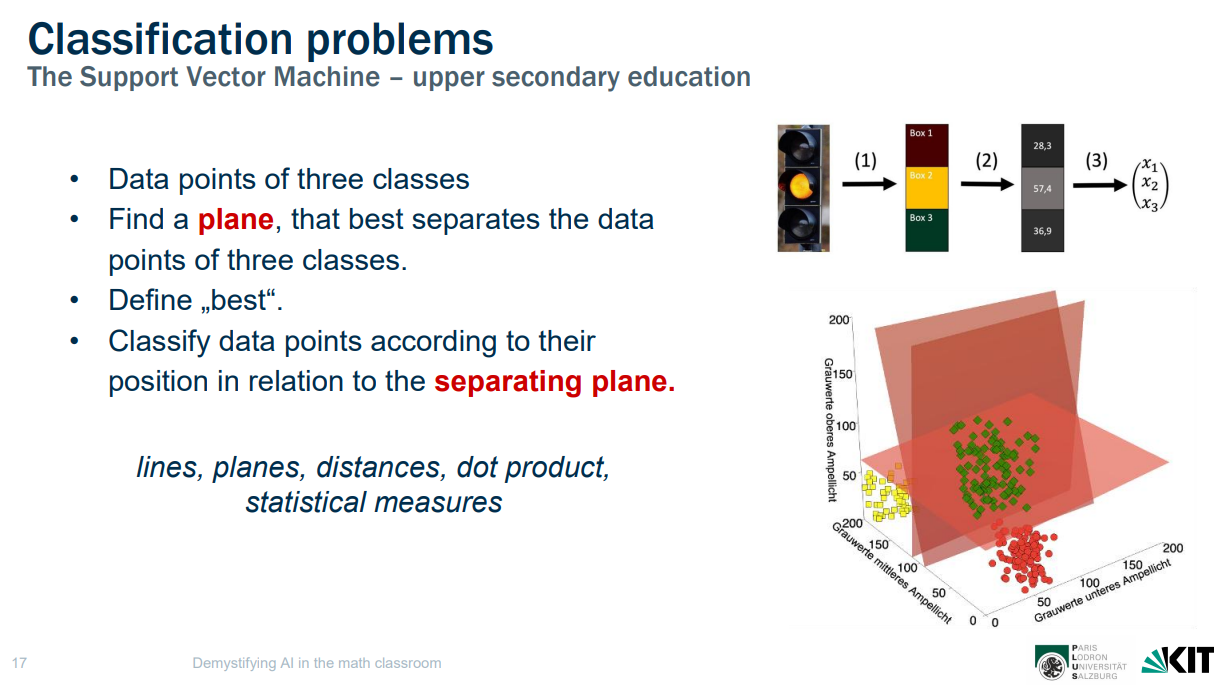

- Explaining how three traffic lights can be expressed as three-dimensional data by using planes

Throughout the presentation, Sarah pointed out where the maths taught was linked to the Austrian and German mathematics curriculum.

Learning about social and ethical issues

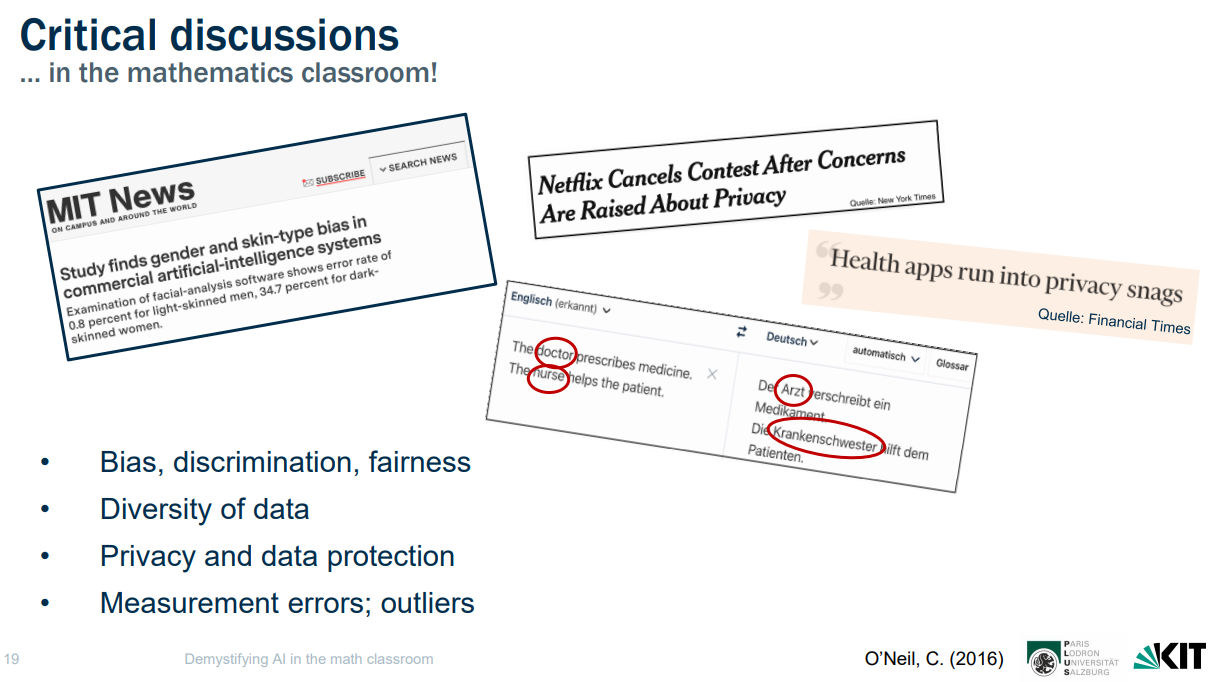

As well as learning about lines, planes, distances, dot product and statistical measures, learners are also engaged in discussing the social and ethical issues of the approach taken. They are encouraged to think about bias, data diversity, privacy, and the impact of errors on people. For example, if the model wrongly predicts a light as green when it is red, then an autonomous car would run through a red traffic light. This would likely be a bigger consequence than stopping at a green traffic light that was mis-predicted as red. So should the best line reduce this kind of error?

To teach the workshops, Sarah explained they have developed interactive Jupyter notebooks, where no programming skills are needed. Students fill in the gaps of example code, explore simulations, and write their ideas for discussion for the whole class. No software needs to be installed, feedback is direct, and there are in-depth tasks and staggered hints.

Learning about regression models: Weather forecasting and the toy artificial neural network

Stephan went on to introduce artificial neural networks (ANNs), which are the basis of generative AI applications like chatbots and image generation systems. He focused on regression models, such as those used in weather forecasting.

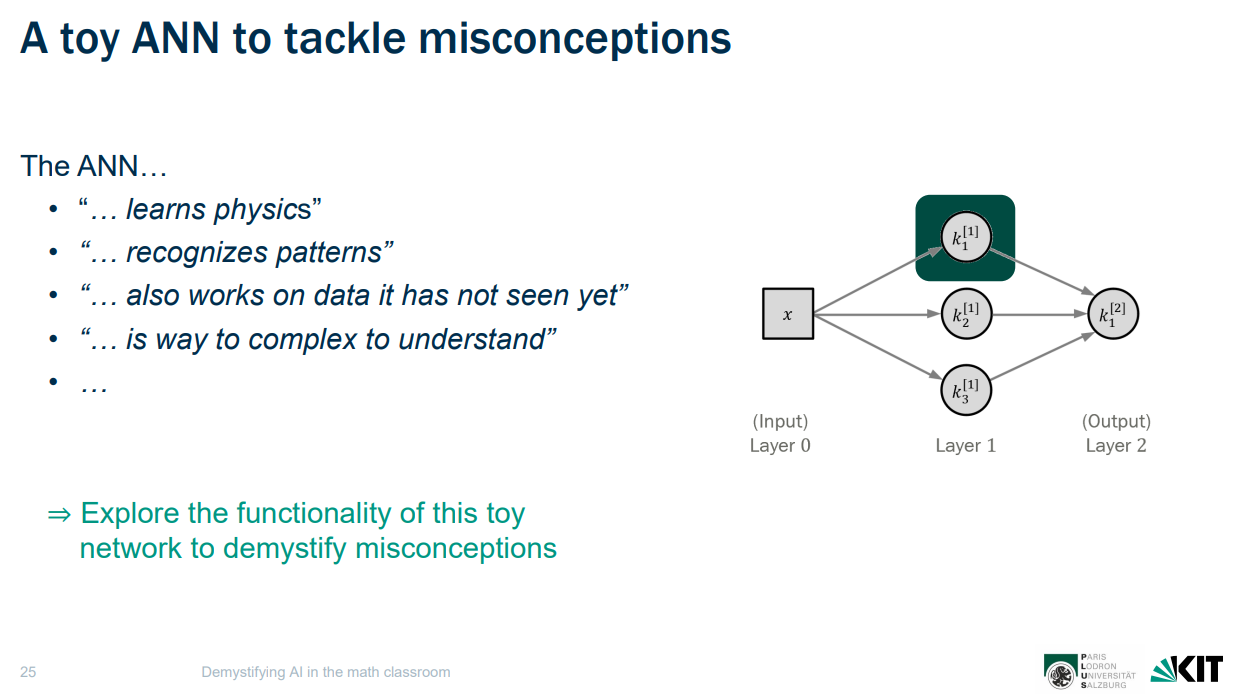

ANNs are very complex. Therefore, to start to understand the fundamentals of this technology, he introduced a ‘toy ANN’ with one input, three nodes, and one output. A function is performed on the input data at each node. With the toy network, the team wants to tackle a major and common misconception: that students think that ANN systems learn, recognise, see, and understand, when really it’s all just maths.

The learning activity starts by looking at one node with one input and one output, and can be described as a mathematical function, with a concatenation of two functions (in this case a linear and activation function). Stephan shared an online simulator that visualises how the toy neural network can be explored as students change two parameters (in this case, weight and bias of the functions). Students then look at the overall network, and the way that the output from the three nodes is combined. Again, they can explore this in the simulator. Students compare simple data about weather prediction to the model, and discover they need more functions — more nodes to better fit the data. The activity helps students learn that ANN systems are just highly adjustable mathematical functions that, by adding nodes, can approximate relationships in a given data set. But the approximation only works in the bounds (intervals) in which data points are given, showing that ANNs do not ‘understand’ or ’know’ — it’s just maths.

Stephen finished by explaining the mutual benefits of AI education and maths education. He suggested maths will enable a deeper understanding of AI, and give students a way to realistically assess the opportunities and risks of AI tools and show them the role that humans have in designing AI systems. He also explained that classroom maths education can benefit from incorporating AI contexts. This approach highlights how maths underpins the design and understanding of everyday systems, supports more effective teaching, and promotes an interdisciplinary way of learning across subjects.

Some personal reflections — which may not be quite right!

I have been researching the teaching of AI and machine learning for around five years now, since before ChatGPT and other similar tools burst on the scene. Since then, I have seen an increasing number of resources to teach about the social and ethical issues of the topic, and there are a bewildering number of learning activities and tools for students to train simple models. There are frameworks for the data lifecycle, and an emerging set of activities to follow to prepare data, compare model types, and deploy simple applications. However, I felt the need to understand and to teach about, at a very simple level, the basic building blocks of data-driven technologies. When I heard the CAMMP team present their work at the AIDEA conference in February 2025, I was entirely amazed and I asked them to present here at our research seminar series. This was a piece of the puzzle that I had been searching for — a way to explain the ‘bottom of the technical stack of fundamental concepts’. The team is taking very complex ideas and reducing them to such an extent that we can use secondary classroom maths to show that AI is not magic and AI systems do not think. It’s just maths. The maths is still hard, and teachers will still need the skills to carefully guide students step by step so they can build a useful mental model.

I think we can simplify these ideas further, and create unplugged activities, simulations, and ways for students to explore these basic building blocks of data representation, as well as classification and representing approximations of complex patterns and prediction. I can sense the beginnings of new ideas in computational thinking, though they’re still taking shape. We’re researching these further and will keep you updated.

Finding out more

If you would like to find out more about the CAMMP resources, you can watch the seminar recording, look at the CAMMP website or try out their online materials. For example, the team shared a link to the jupyter notebooks they use to teach the workshops they demonstrated (and others). You can use these with a username of ‘cammp_YOURPSEUDONYM’, where you can set ‘YOURPSEUDONYM’ to any letters, and you can choose any password. They also shared their toy ANN simulation.

The CAMMP team are not the only researchers who are investigating how to teach about AI in maths lessons. You can find a set of other research papers here.

Join our next seminar

In our current seminar series, we’re exploring teaching about AI and data science. Join us at our last seminar of the series on Tuesday, 27 January 2026 from 17:00 to 18:30 GMT to hear Salomey Afua Addo talk about using unplugged approaches to teach about neural networks.

To sign up and take part, click the button below. We’ll then send you information about joining. We hope to see you there.

The schedule of our upcoming seminars is online. You can catch up on past seminars on our previous seminars page.

2 comments

Jump to the comment form

hafsah

very informative and fun to learn about xx

fathimah

soo interesting…….