A research-led framework for teaching about models in AI and data science

Research indicates that teaching learners to use and create with data-driven technologies such as AI and machine learning (ML) requires an entirely different approach for solving problems compared to traditional programming activities.

In this blog, we share the new data paradigms framework that we have developed through research and used to help improve our understanding about how to teach and learn about AI and data science. We also invite you to register your interest in participating in our next collaborative study on the topic.

Knowledge-based approaches to systems design

Let’s start by highlighting an important distinction between different approaches to designing systems. In a knowledge-based approach to system design, a set of rules (e.g., if-then statements) are written for the system to execute. Every rule is explicitly defined. This approach is called ‘rule-based’, ‘symbolic’, or ‘logic-based’. For example, a developer could create a program that simulates dialogue by writing specific lines of code to handle a greeting, such as “IF user says “Hello” THEN output “Hi!”. If the user types “Greetings!” instead, the program fails because it has no rule for that specific word.

Knowledge-based models are often said to be explainable by design. This means the logic is accessible and interpretable and developers can trace the exact steps taken to produce an output. For example, if developers manually classify restaurant reviews as positive or negative using a pre-defined set of criteria, the rules their restaurant classifying system follows are entirely explicit, and the path from input to output is clear and explainable.

Data-driven approaches to systems design

By contrast, in a data-driven approach to system design developers do not write specific rules. Instead, they collect lots of data and train a model. In the dialogue simulator example, they would collect hundreds of examples of greetings and train a model to the pattern of a greeting. If the user types “Greetings!”, the system generates a response based on the patterns in its training data.

Data-driven models are often opaque. In other words, the internal workings of these ML models are hidden. While we can see our input and the system’s output, the internal mathematical process is so complex — often involving layers of calculations and abstractions — that we cannot simply “explain” why a specific output was produced. For example, developers can create a classification model by training a neural network using thousands of images. Due to the large quantity of data used to train the model, and complex internal parameters and hidden layers, developers and users of the system cannot understand or explain the logic or features that lead to a specific output. These kinds of models are often referred to as a “black box” (as opposed to a “glass” or “clear” box).

Comparing knowledge-based and data-driven approaches

Researchers have argued that the move from knowledge-based (or rule-based) programming to data-driven system design represents a paradigm shift and creates unique challenges for educators. The challenge is helping students shift from the expectation that a system produces a single ‘right’ answer — characteristic of traditional rule-based programming — toward an understanding that systems trained on large quantities of data produce outcomes that aren’t always fixed or explainable. If the current instruction in the classroom still relies heavily on traditional rule-based programming approaches, we might be setting students up for misconceptions.

Data paradigms: A framework for analysing data science education approaches

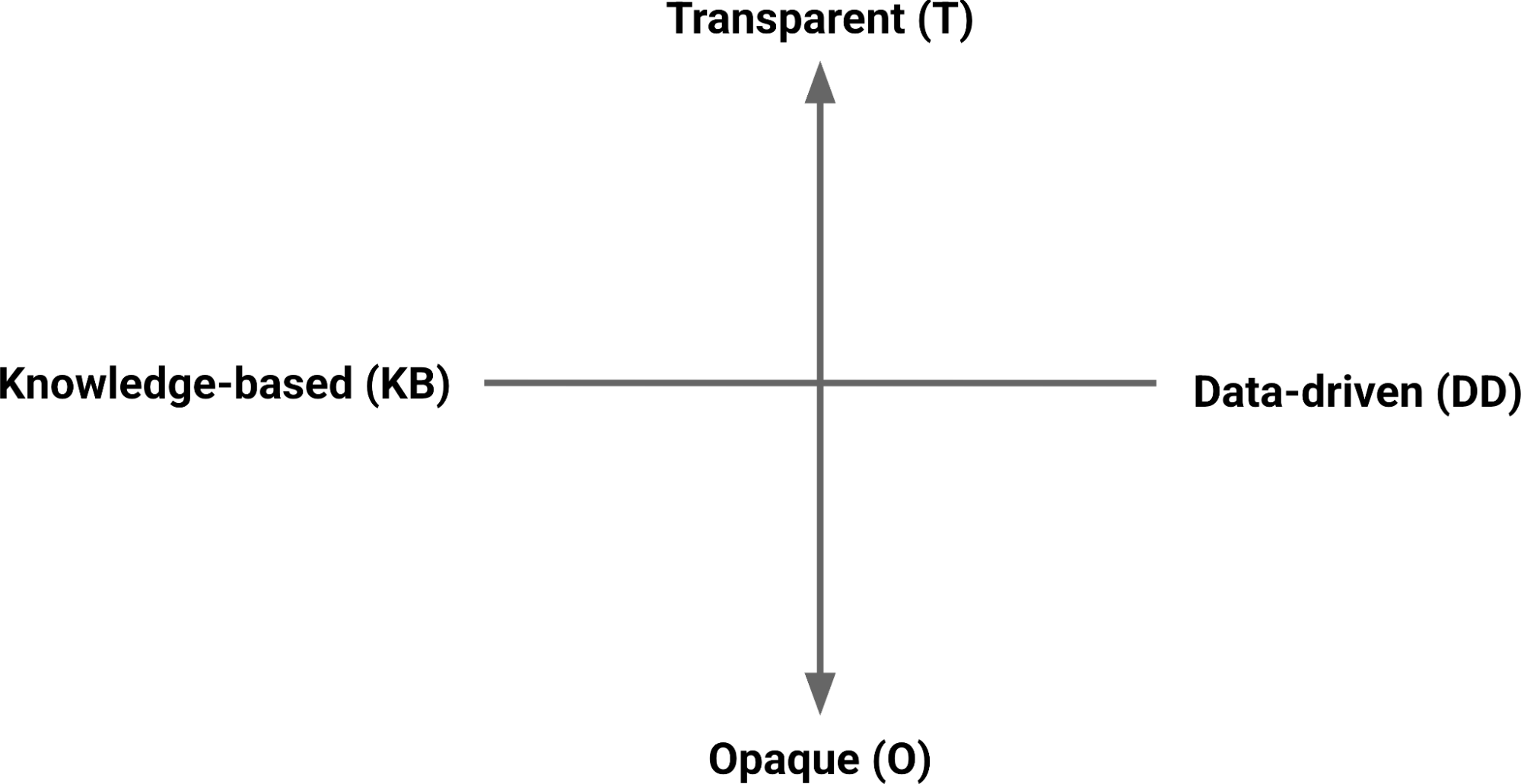

In our research work on AI and data science at the Raspberry Pi Computing Education Research Centre, we analysed 84 research studies about the teaching and learning of data science. We categorised learning activities used in the studies to understand whether they were (i) knowledge-based or data-driven, and (ii) the extent to which the underlying models used were transparent or opaque. This led us to define four distinct data paradigms:

- Knowledge-based and transparent (KB + T): Activities in this paradigm are ones where students write rules for systems, or work with systems that use rules, where the logic is fully explainable by design. For example, if students manually classify data (e.g. creating simple ‘if-then’ statements to predict an outcome), the path from input to output is clear.

- Data-driven + Transparent (DD + T): In this paradigm, activities involve students working with models trained on data, but the trained model’s logic remains explainable and interpretable. For example these could be models using k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm to group data points based on proximity, or using linear regression to predict a trend. Even though the model produces an output, the student can look at the inner workings of the model and see how the decision is made.

- Data-driven + Opaque (DD + O): This paradigm’s activities require students to work with data-driven ML models where the models’ internal logic is hidden, for example an image classification model using a type of neural network (e.g. CNN). The model produces an output (e.g. classifying an image as ‘This is a dog’), but the student cannot inspect the system to find a rule or clear path explaining why that specific output was produced. To understand these systems, it’s necessary to use additional testing and evaluation tools.

- Knowledge-based + Opaque (KB + O): Activities in this paradigm would involve systems with human-written rules that are not explainable. In our review of K–12 activities, we found no examples of activities within this paradigm.

The data paradigms framework helps us to distinguish between different kinds of modeling activities students take part in and how instructional approaches could be classified across one or more paradigms. For instance, we found that most data-driven activities were also opaque (DD + O), usually meaning that students collected and used data to train a model, but how the system worked was opaque. This pattern, where the data is visible but the model is not explainable, risks students forming misconceptions about the capabilities and limitations of data-driven systems. Without understanding how outputs are generated, students may expect data-driven ML systems to operate like fully explainable (or transparent) ones.

We think that lessons are needed in the data-driven opaque (DD + O) quadrant to explicitly teach students about how data-driven systems work and the role they play in everyday contexts. However, when teaching data-driven opaque (DD + O) activities, learners’ attention needs to be directed to concepts such as model confidence, data quality, and model evaluation. Since an ML model is not inherently explainable, we need to teach students to use post-hoc explanation methods, such as testing different inputs to see how a system’s output changes. To prepare students for this learning experience, we think that first introducing activities about rule-based systems (knowledge-based + transparent; KB + T) or simple data exploration, such as linear regression or data visualisation (data-driven + transparent; DD + T) may serve as a ‘bridge’ to understanding data-driven modeling by helping students to distinguish between systems built from specific logical rules and systems trained on data.

We believe the idea of data paradigms can serve as a way of framing teaching activities about data science and help educators and students to consider the transition between different paradigms when engaging with the systems we interact with every day.

Teachers in England, participate in our new study

KS2 teachers, participate in our new study!

We’re launching a new study to explore how to teach learners aged 9 to 11 about data-driven computing. The study will take place in collaboration with KS2 teachers (Y4/Y5/Y6) in England, Scotland and Wales and look at:

- What key ideas pupils need to understand

- How teachers currently approach topics related to data-driven computing

- How pupils make sense of data and probability

Our goal is to find practical ways to help teachers build children’s confidence in working with data in computing lessons. The study will be collaborative, with two workshops held throughout 2026, and we’re inviting KS2 teachers (Y4/Y5/Y6) to take part.

You can express your interest in participating by filling in this form:

No comments

Jump to the comment form