How to put data first in K–12 AI education by using data case studies

In Germany, as in many countries, AI topics are rapidly entering formal computer science education. Yet, this haste often risks us focusing on fleeting technological developments rather than fundamental concepts. As computer science educator Viktoriya Olari, from Free University of Berlin, discovered in her research, the fundamental role of data, which powers most modern AI systems, is critically underestimated in many existing frameworks. If students are to become responsible designers of such systems, they can’t afford to treat AI as an opaque box. Rather, they must first master the messy, human process that begins with the data itself.

In our October research seminar, Viktoriya shared the results of her work over the last four years on how schools can shift the focus from the latest technologies to the underlying data. Her research offers a clear structure for what young people should learn about data and how teachers can make it work inside ordinary classrooms.

Why begin with data?

Viktoriya’s analysis of existing AI education frameworks found the data domain is underrepresented, with essentials such as data cleaning often not addressed at all. She argues that, because modern AI systems are data driven, students need both language and routines for working with data: being able to name concepts like training vs test data, data quality, and bias, and to explain practices such as collection, cleaning, and pre-processing. That’s the rationale for teaching data concepts and practices first, and then placing modelling inside an explicit, staged lifecycle.

Her talk presented this argument in the German school context, where AI topics are entering state curricula quickly. Her critique targets how existing frameworks fail to address data and how that gap undermines responsible evaluation and design. The proposed model centres data by pairing an eight-stage, data-driven lifecycle with a curated set of key concepts and practices, and by making “data-based judgment skills” a key outcome.

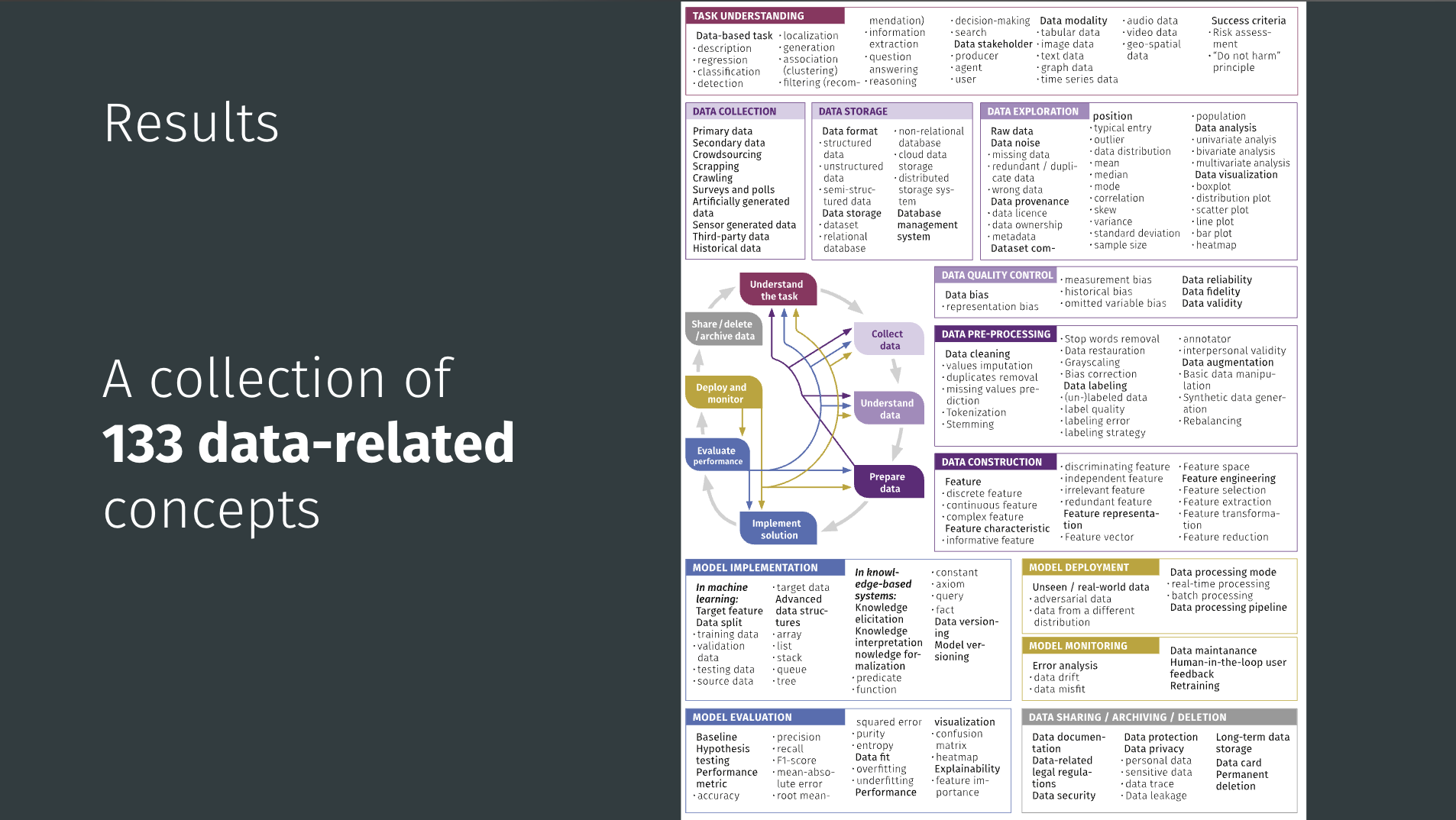

Viktoriya’s work organises this understanding into two foundational components: data concepts (the vocabulary, e.g. training/test data, data quality, overfitting) and data practices (the actions, e.g. collect, clean, train, evaluate).

A lifecycle for learning

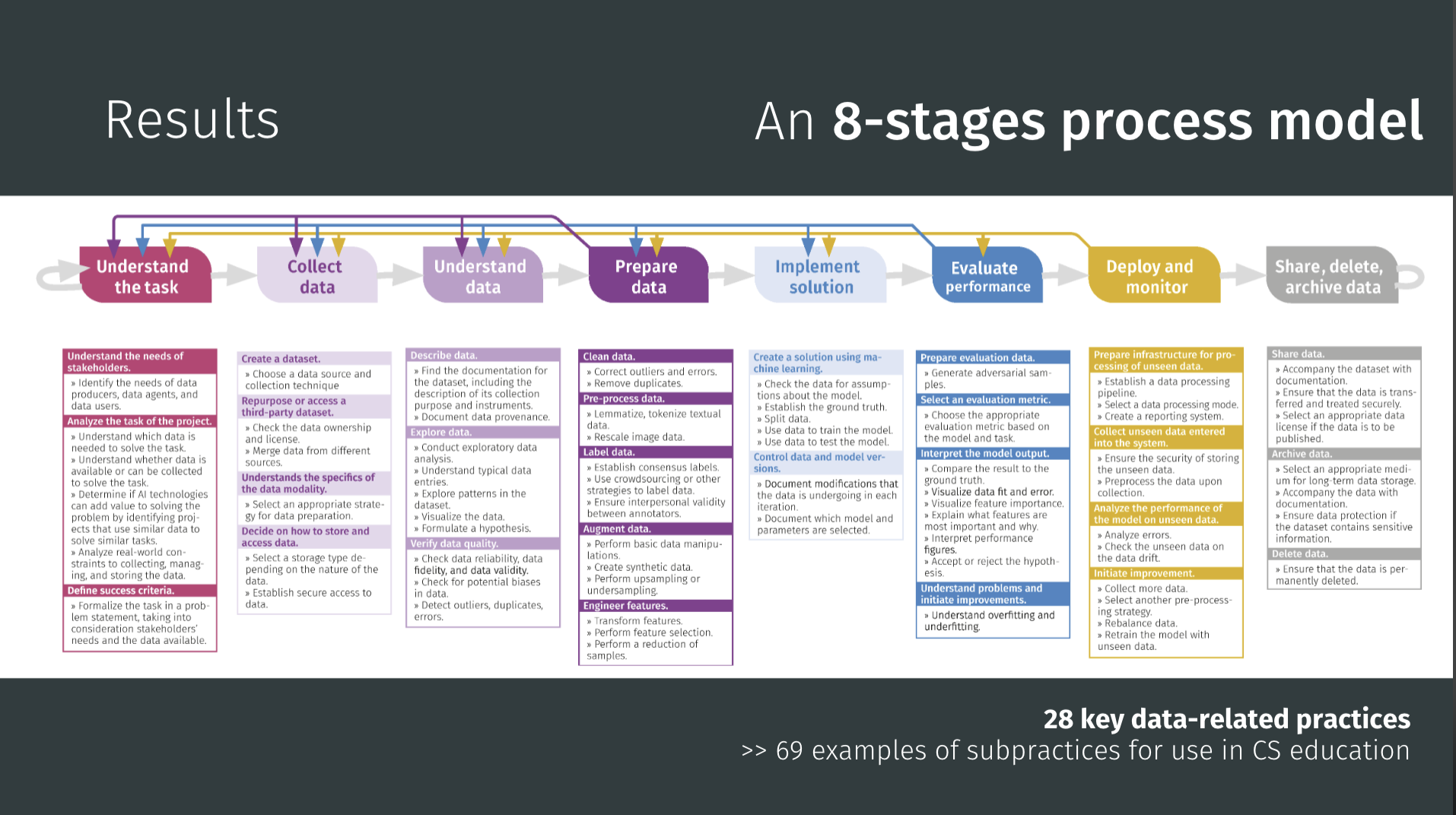

Viktoriya’s framework is built around an eight-stage data lifecycle, stretching from defining a task through gathering, preparing, modeling, evaluating, and finally sharing or archiving results. Inside that backbone she has identified two layers of learning targets:

- Data concepts – roughly a hundred ideas that give teachers and students a common language, from “training vs. test data” and “bias” to “features”, “labels”, and “provenance”.

- Data practices – 28 kinds of hands-on work (and 69 subpractices) that materialise those ideas: for instance collecting, cleaning, splitting datasets, checking quality, training and evaluating models, and handling privacy and deletion responsibly.

More details are available in her work on data-related concepts and practice.

Viktoriya’s 8-stage process model of the data-driven lifecycle. It serves as a guide for curriculum developers and teachers, outlining 28 key data-related practices and providing 69 examples of subpractices for use in K–12 computer science education.

A collection of 133 key data-related concepts. These concepts are organised according to the eight stages of the data-driven lifecycle and provide the foundational vocabulary for teaching AI education.

Making it teachable

Viktoriya’s team set out to redesign the format so that real data work could happen within ordinary lessons. They ended up with three “Data Case Study” architectures, each using authentic datasets and domain questions. The materials are supported by Orange 3, an unplugged machine learning and data visualisations tool familiar to the teachers participating. Variants emerged across three design cycles to address specific challenges, but teachers choose among them based on learning objectives and class context.

- Bottom-up: Students create a workflow step by step (e.g. import, inspect, clean, transform, split, train, evaluate). This approach is excellent for procedural fluency, but teachers reported an over-emphasis on operating Orange and too little reflection on the lifecycle unless explicit reflection is added.

- Top-down: Students start from a prepared workflow, read plots, infer the role of each branch, identify issues in the data/practices, and justify changes. This architecture directly counters the reflection gap seen in bottom-up and leans into reasoning rather than routine.

- Puzzle-like: Using “widgets,” visualisations of data tables, that stand for parts of a data pipeline, students rebuild a valid flow collaboratively. This encourages discussion, works without devices, and makes thinking visible.

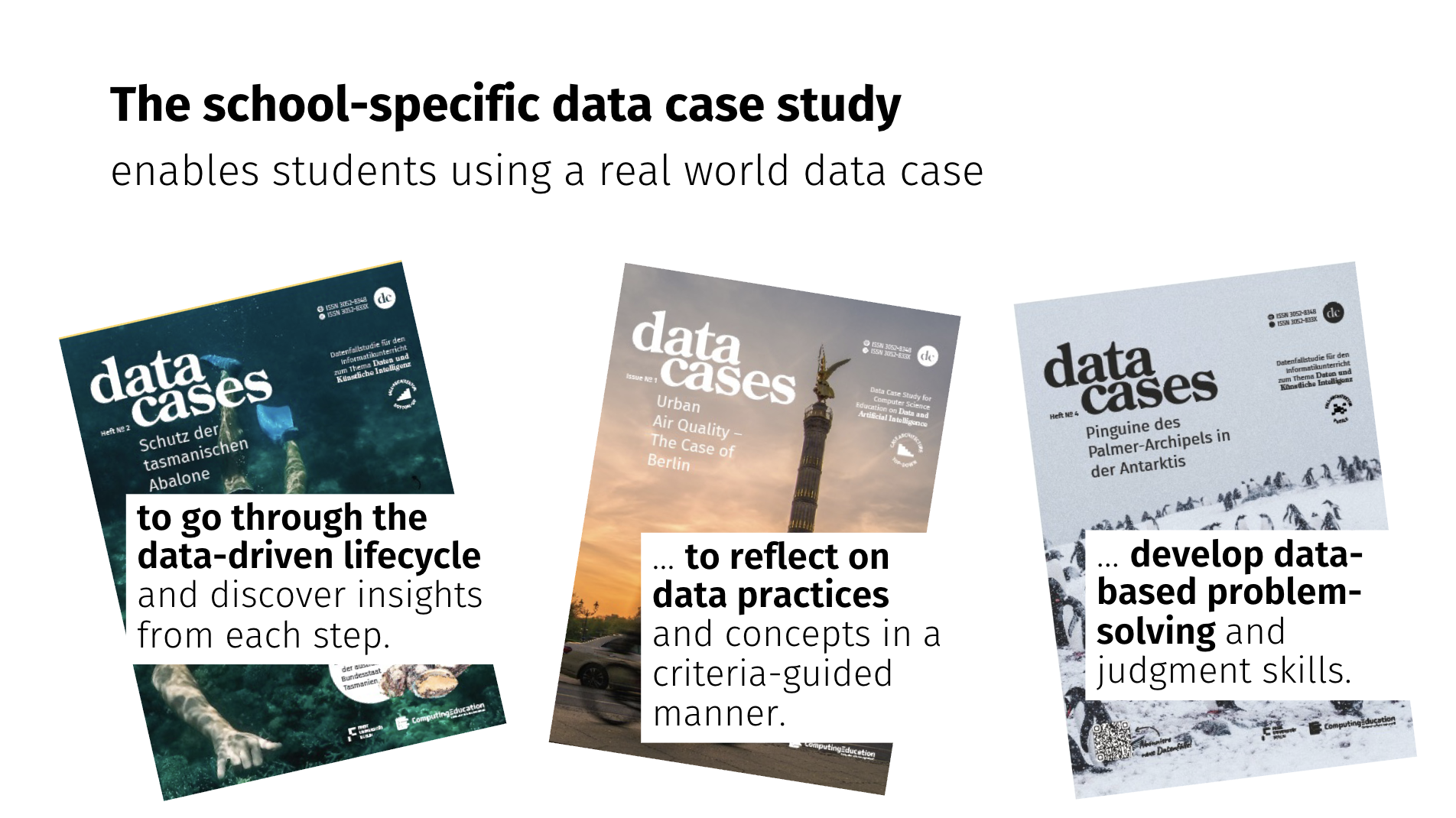

The data case study method uses real-world data and context to help students achieve three key learning outcomes: go through the data-driven lifecycle, reflect on data practices and concepts in a criteria-guided manner, and develop data-based problem-solving and judgment skills.

What happened in the German classrooms

Viktoriya’s team ran three design cycles with small groups in Germany, with students aged 14 to 15. Each cycle lasted around 48 hours of teaching. Because participating teachers already knew Orange 3, the emphasis was on pedagogy rather than software training.

The projects drew on manageable real-world data: spreadsheets, time-series sets, a few geographical samples. Two examples are:

- Forecasting Berlin air quality – Students explored how data quality, feature choice, and evaluation metrics shape predictions, then argued which model best answered the civic question.

- Classifying Tasmanian abalone – A deceptively simple dataset that invites talk about imbalance, feature engineering, and what counts as “good enough” accuracy.

Some groups experimented with collecting their own sensor data, a plan that occasionally failed when the hardware didn’t cooperate. However, even that became part of the lesson: reliability, risk, and missing data are real features of data science, not mistakes to hide.

Student work reflected the three architectures. In the bottom-up groups, guided builds produced complete workflows and concise reflections, while top-down groups submitted annotated screenshots and critiques, and the puzzle-based lessons ended with posters and verbal presentations. Across them all, assessment focused on reasoning: not whether the “right” model appeared, but whether students could explain the stage they were in and justify their choices.

Teaching resources

Everything Viktoriya described is open and classroom-ready (currently in German). The computingeducation.de/proj-datacases hub hosts teacher guides, student tasks, and sample Orange 3 files. The growing library of data cases covers topics from climate data to air quality analytics.

Why it matters now

In the UK, a curriculum review has been recently released and along with the Government’s response. Across Europe and beyond, education systems are racing to add AI content to their curricula. Tools will come and go, and benchmarks will keep moving. What endures is the capacity to reason about data: to know what stage of work you’re in, what evidence supports your decisions, and what trade-offs you’re making. That is why Viktoriya’s contribution is unique — it gives teachers a map, a shared vocabulary, and practical ways to make data visible and the focus of discussion in schools.

You can read this blog to see how we’ve used Viktoriya’s framework in our work designing a data science curriculum for schools.

Join our next seminar

Join us at our seminar on Tuesday 27 January from 17:00 to 18:30 GMT to hear Salomey Afua Addo talk about how to teach about neural networks in Junior High Schools in Ghana.

To sign up and take part, click the button below. We’ll then send you information about joining.

We hope to see you there. This will be the final seminar in our series on teaching about AI and data science — the next series focuses on how to teach about applied AI across subjects and disciplines.

You can view the schedule of our upcoming seminars, and catch up on past seminars on our previous seminars page.

Teachers in England, take part in our new data science study

WKS2 teachers, participate in our new study!

We’re launching a new study to explore how to teach learners aged 9 to 11 about data-driven computing. The study will take place in collaboration with KS2 teachers (Y4/Y5/Y6) in England, Scotland and Wales and look at:

- What key ideas pupils need to understand

- How teachers currently approach topics related to data-driven computing

- How pupils make sense of data and probability

Our goal is to find practical ways to help teachers build children’s confidence in working with data in computing lessons. The study will be collaborative, with two workshops held throughout 2026, and we’re inviting KS2 teachers (Y4/Y5/Y6) to take part.

You can express your interest in participating by filling in this form: rpf.io/data-science-study-blog

1 comment

Jump to the comment form

I am very excited

I am very excited